PROXY MONITOR 2016

FINDING 3

Political Spending and Lobbying

By James R. Copland and Margaret M. O'Keefe

ABOUT PROXY MONITOR

The Manhattan Institute's Proxy Monitor database, launched in 2011, is the first publicly available database cataloging shareholder proposals and Dodd-Frank-mandated executive-compensation advisory votes[1] at America's largest publicly traded companies. The database is overseen by Margaret M. O'Keefe, who has more than two decades' experience in executive-compensation, corporate-governance, and proxy-advisory consulting. This is the 39th publication in a series of findings and reports written solely or jointly by Manhattan Institute legal-policy director James R. Copland, each drawing upon information in the database to examine shareholder activism in which investors attempt to influence corporate management through the shareholder-proposal process[2].

|

Introduction

In 2016, a shareholder proposal concerning corporate political spending received majority shareholder support over board opposition—the first such result among 455 such proposals introduced over the last 11 years. There was no overall increase in shareholder support for political-spending-related proposals, however, notwithstanding increased political pressures.

Ever since the Supreme Court's 2010 decision in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission[3]—which determined that independent political expenditures were speech protected by the First Amendment, even if funded by for-profit corporations—corporate political engagement has been much debated. The decision drew a rebuke from President Obama in his 2010 State of the Union address, with many of the Supreme Court justices in front of him.[4] In 2011, several U.S. senators, including 2016 Democratic presidential candidate Bernie Sanders of Vermont, proposed amending the First Amendment in response.[5] Also in 2011, several professors of corporate and securities law petitioned the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), seeking to have the agency establish rules for publicly traded companies to disclose fully their political spending, direct and indirect.[6] This petition has become increasingly politicized in 2016, as U.S. senators have openly clashed with the chairman of the SEC, Mary Jo White, over the agency's failure to respond to it;[7] and some of these same senators have even seized on the issue to block President Obama's new appointees to the SEC.[8]

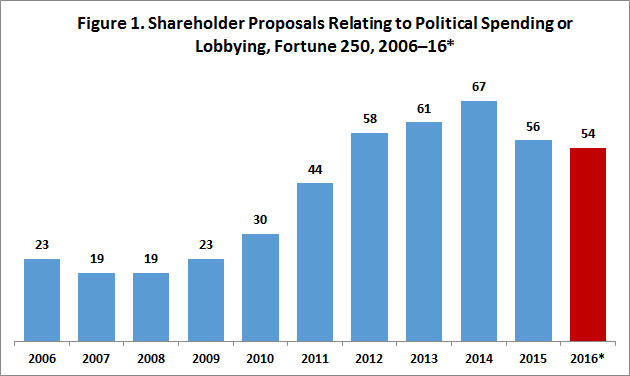

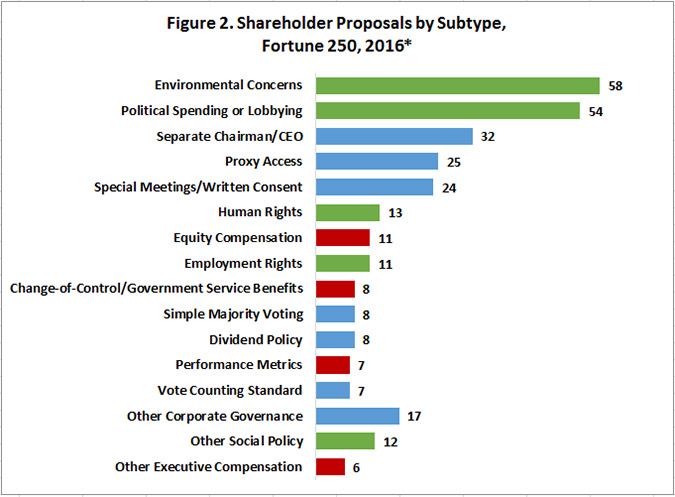

The fight over the professors' SEC rulemaking petition comes against a backdrop of long-standing efforts to influence corporate behavior on the subject by certain shareholder activists who take advantage of the agency's rules[9] that allow owners of equity securities to place items on the proxy ballots of publicly traded corporations, to be voted on at their annual meetings, if the sponsoring investors have owned $2,000 or more company shares for at least one year.[10] And in 2003, Bruce Freed, a former Democratic congressional staffer, founded an organization, the Center for Political Accountability (CPA), exclusively to "campaign for corporate political disclosure and accountability."[11] Dating back to 2006, the first year covered in the Proxy Monitor database, at least 19 shareholder proposals on companies' political engagements have been placed on Fortune 250 corporations' proxy ballots each year (Figure 1). The number of such proposals started to increase after Citizens United, peaking at 67 in 2014, before falling somewhat in 2015 and 2016. Nevertheless, as was the case last year, proposals related to corporate political spending or lobbying were the second-most common class of shareholder proposals introduced in 2016 (Figure 2).

*In 2016, for 228 of 250 companies with annual meetings scheduled through the end of June

Source: ProxyMonitor.org database

*228 of 250 companies with annual meetings scheduled through the end of June

Source: ProxyMonitor.org database

From 2006 through 2015, 401 shareholder proposals were introduced at Fortune 250 companies. Not one received majority shareholder support over board opposition.[12] In 2016, a board-opposed proposal on political spending did receive majority shareholder support—a May 5 proposal submitted by the City of Philadelphia Public Employees Retirement System to Fluor Corporation,[13] the largest engineering and construction company in the Fortune 500. This voting result may be company-specific and anomalous, however, as there is no broader uptick in shareholder support for political spending and lobbying proposals in 2016, relative to last year. This finding explores 2016 shareholder-proposal activism related to political spending and lobbying in historical and recent context.

Focus: Shareholder Activism on Corporate Political Spending and Lobbying

Background

The 2016 proxy season began with an atypically politicized environment around the issue of corporate political spending and lobbying. On Thursday, April 7, two Democratic senators—Chuck Schumer of New York and Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts—held up the confirmation of President Obama's two most recent nominees to the five-member Securities and Exchange Commission.[14] Schumer accused the president's nominees of "fence-sitting" on whether they would support taking up a rulemaking petition,[15] submitted to the SEC by several law professors, which calls on the agency to mandate new corporate disclosures on political spending.[16] In a June 14 hearing before the U.S. Senate's Committee on Banking, Housing and Urban Affairs, Schumer and Warren upbraided Mary Jo White, chairman of the SEC, on the same subject.[17] Warren complained that under White's leadership, the agency was "mak[ing] life easier for corporations and harder for investors," while Schumer went so far as to accuse White of "hurting America."[18]

Politics-Related Shareholder-Proposal Activism: 2006–16

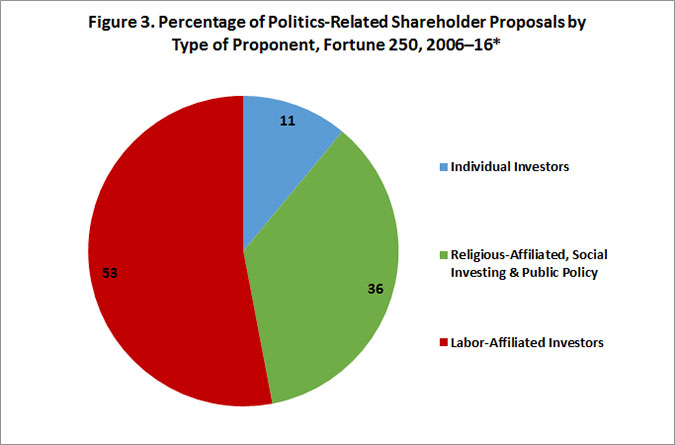

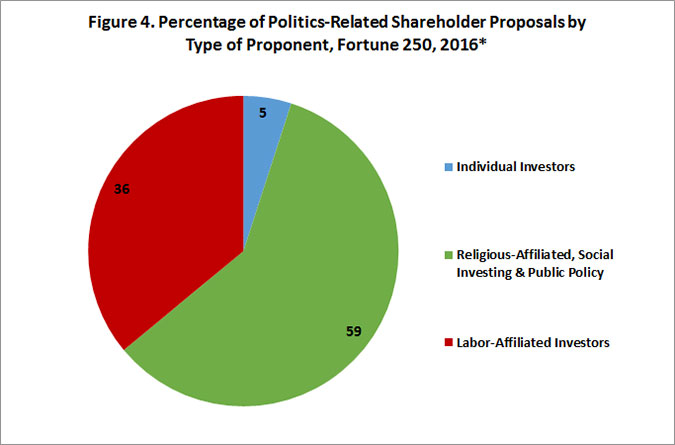

Since 2006, a majority of shareholder proposals involving corporate political spending or lobbying (53 percent) have been sponsored by labor-affiliated institutional investors, generally either pension funds for state or municipal employees or multiemployer pension funds affiliated with private labor unions (Figure 3). The second-most common sponsors of politics-related shareholder proposals have been institutional investors with a social or policy orientation, chiefly social-investing funds that focus on "socially responsible investing"[19] or religious-affiliated investors (typically, the pension funds of Catholic orders of nuns or other church-based institutions).[20] In 2016, such social- or policy-related investors constituted a majority (59 percent) of all politics-related shareholder-proposal sponsors (Figure 4).

*In 2016, for 228 of 250 companies with annual meetings scheduled through the end of June

Source: ProxyMonitor.org database

*228 of 250 companies with annual meetings scheduled through the end of June

Source: ProxyMonitor.org database

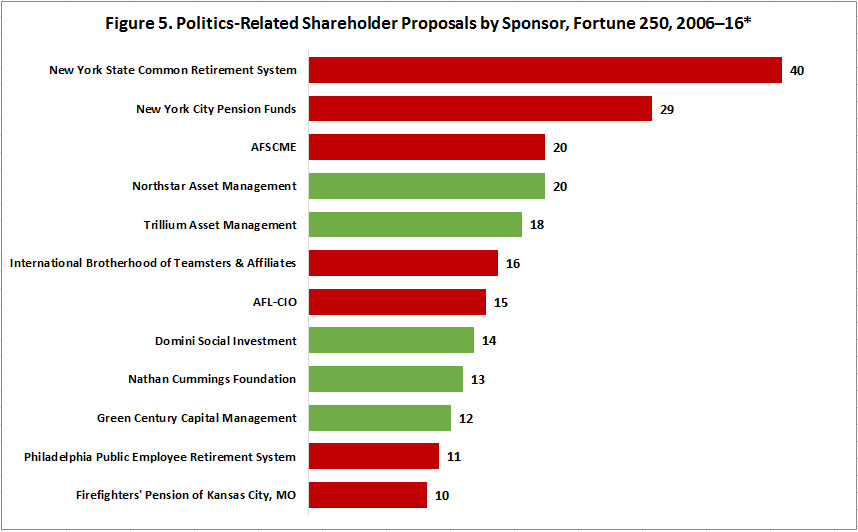

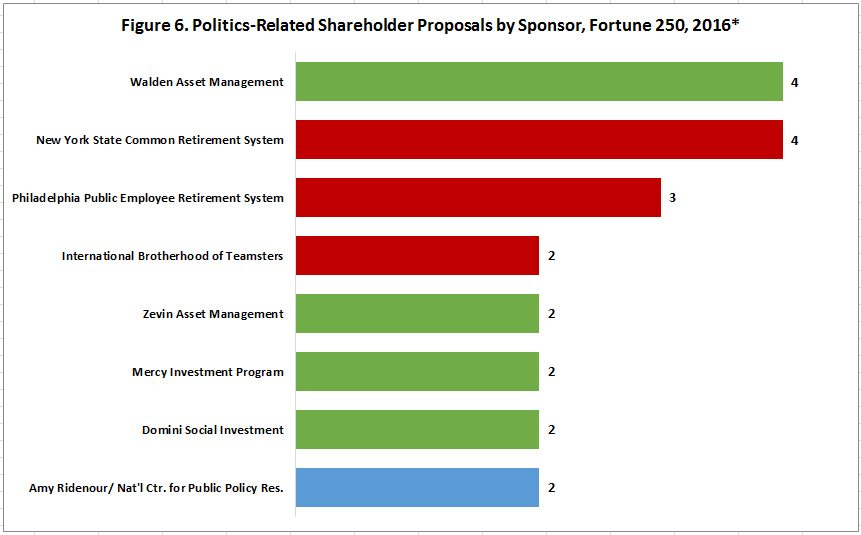

The pension funds for New York State and New York City's public-employee retirees have been the shareholders most regularly sponsoring these types of proposals, followed by the American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees (AFSCME), which represents various public employees nationwide (Figure 5). The social-investing funds Northstar Asset Management and Trillium Asset Management have also been regular sponsors of shareholder proposals related to political spending or lobbying. In 2016, the New York State fund has sponsored four shareholder proposals that made Fortune 250 companies' proxy ballots, as has the social-investing fund Walden Asset Management; the public-employee pension fund for Philadelphia has sponsored three (Figure 6).

*In 2016, for 228 of 250 companies with annual meetings scheduled through the end of June

Source: ProxyMonitor.org database

*228 of 250 companies with annual meetings scheduled through the end of June

Source: ProxyMonitor.org database

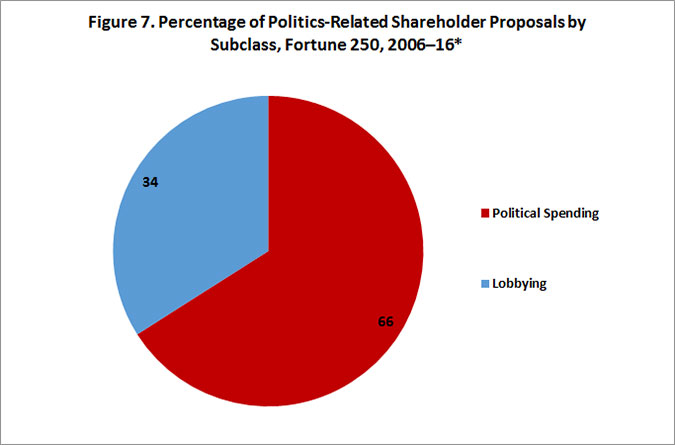

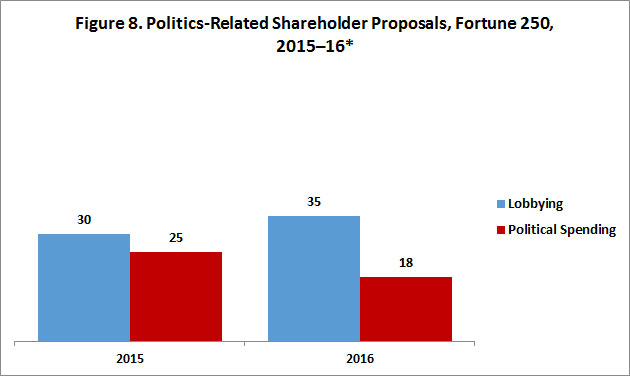

Just as the sponsors of shareholder proposals relating to political spending or lobbying have shifted over time, so, too, have their subject matters. From 2006 through 2016, about two-thirds of all politics-related shareholder proposals involved corporate political spending (Figure 7). Most typically, these have followed a template developed by the CPA that asks companies to disclose political-spending guidelines, all payments to trade associations and other tax-exempt organizations that are used for political purposes, the amounts contributed, and the identities of corporate officers involved in the expenditure decisions. In recent years, sponsors of shareholder proposals have more commonly sought to target corporate payments to groups involved in lobbying activities, including "direct and indirect lobbying" and "grassroots lobbying communications," at the local, state, and federal levels.[21] In 2015, such lobbying-related proposals outnumbered those focused on political spending; in 2016, almost twice as many lobbying-related proposals as political-spending proposals were on Fortune 250 companies' proxy ballots (Figure 8).

*In 2016, for 228 of 250 companies with annual meetings scheduled through the end of June

Source: ProxyMonitor.org database

*In 2016, for 228 of 250 companies with annual meetings scheduled through the end of June

Source: ProxyMonitor.org database

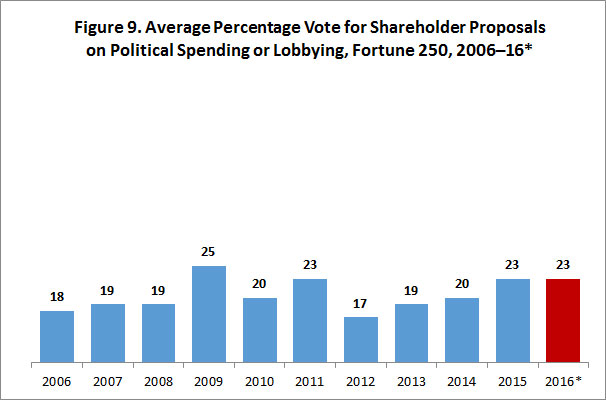

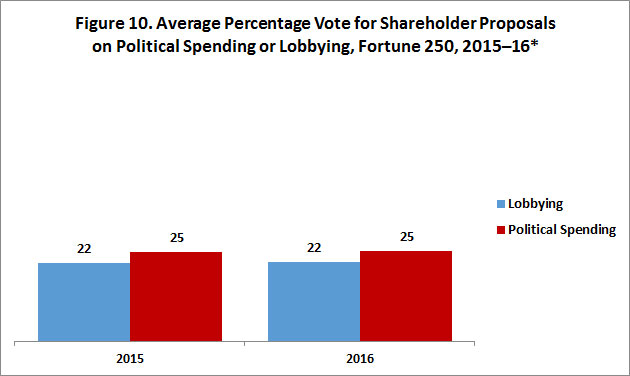

Voting Results and Analysis

As noted earlier, there is no discernible upward trend in 2016, relative to 2015, in shareholder support for proposals related to companies' political spending or lobbying; shareholder support for each class of proposal averaged 23 percent in each year (Figure 9).[22] The overall vote totals for 2015 and 2016 are on the high side, relative to years 2006 through 2014, but this variation is largely attributable to variations in the mix of proposal types: in earlier years, certain proposals were commonly introduced that received low-single-digit support—such as those seeking a 75 percent shareholder vote to authorize corporate political spending or to prohibit such spending outright—but have been less commonly filed in recent years, either because they failed to meet minimum shareholder support thresholds or because their sponsors decided not to introduce such proposals again for other reasons. Disaggregating politics-related shareholder proposals into those focused exclusively on political spending and those focused exclusively on lobbying shows the same year-over-year trend, as variations in support levels amount to rounding errors (Figure 10). Narrowing down the class of shareholder proposals to those tracking the CPA's model disclosure language on political spending, the 13 shareholder proposals coming to a vote in 2016 averaged 31 percent shareholder support, up marginally from 30 percent in 2015; this difference is wholly attributable to the 52 percent support received by the successful proposal at Fluor.

*In 2016, for 219 of 250 companies holding annual meetings by June 10

Source: ProxyMonitor.org database

*In 2016, for 219 of 250 companies holding annual meetings by June 10

Source: ProxyMonitor.org database

The Fluor proposal, tracking the general CPA language, sought disclosure of "[p]olicies and procedures for making, with corporate funds or assets, contributions and expenditures (direct or indirect) to (a) participate or intervene in any political campaign on behalf of (or in opposition to) any candidate for public office, or (b) influence the general public, or any segment thereof, with respect to an election or referendum," as well as disclosure of amounts given to each identified recipient and the corporate officer responsible for decision making.[23] The same proposal sponsor, the Philadelphia Public Employee Retirement System, sponsored the same proposal in 2015, when it received 31 percent shareholder support. Thus, the 2016 results at Fluor may be idiosyncratic to the company. As a major construction company, Fluor is heavily involved in government-contracting work,[24] which may make shareholders particularly sensitive to its political engagement.[25] Moreover, the company's market capitalization fell more than 43 percent from the record date for its 2014 annual meeting and its 2016 annual meeting, when it missed its earning target.[26] A proposal by the New York State Common Retirement Fund on greenhouse gas emissions also received more than 40 percent support at Fluor, though the company's advisory shareholder vote on executive compensation comfortably passed, with almost 94 percent shareholder support.

Whatever the reasons for Fluor's shareholder vote, the fact remains that it is the first time in the 11-year history of the Proxy Monitor database that a shareholder proposal related to political spending or lobbying has received majority shareholder support over board opposition—among 455 politics-related proposals to make company's proxy ballots. In addition, the shareholder support received by this class of shareholder proposals is less robust than it might appear. A "for" voting recommendation by the leading shareholder-advisory firm Institutional Shareholder Services (ISS) is associated with a 15-percentage-point increase in the shareholder vote for the proposal, controlling for other factors[27]—even ignoring support from Glass Lewis, the second-largest proxy-advisory firm, and other proxy advisors—because "[s]maller institutional investors [are] likely to ‘follow' ISS."[28] ISS has a stated policy of being generally "for" shareholder proposals related to disclosing a company's political spending.[29] (Given its business incentives, ISS's recommendations tend to be "systematically biased in favor of shareholder-proposal activism"; "ISS receives significant revenues from social investment vehicles and labor-union pension funds, which gives the company an incentive to favor ‘socially responsible' investing proposals.")[30]

The Fluor vote demonstrates that shareholders, if they want to, can press companies' leadership to disclose more about their political activities. The overall shareholder voting record, however, strongly counsels against any action by the SEC mandating a rule; it is hard to argue that it is in the interests of shareholders to force companies to disclose information that shareholders themselves have consistently opposed disclosing.[31]

The CPA boasts that as a result of its efforts, "[a] number of companies are curbing their payments to trade associations and 501(c)(4) nonprofit groups and restricting their political spending"[32]—an outcome that it is easy to see may not be in corporate shareholders' interests.[33] Such efforts are part of a broader effort to silence corporate speech or other speech inimical to progressive political agendas.[34]

Notwithstanding broad shareholder opposition, many companies have responded to shareholder proposals on corporate political spending by negotiating with such proposals' sponsors for various disclosure rather than facing a shareholder vote. New York State comptroller Thomas DiNapoli, an elected Democrat who is the sole fiduciary of the New York State Common Retirement Fund—and who has made targeting companies' political spending a centerpiece of his tenure (with dubious results for the fund)[35]—has touted just these outcomes. Thus, shareholder-proposal activism in this area deserves continuing scrutiny, even if the SEC continues to resist political pressure to engage in rulemaking on the subject.

ENDNOTES

- Under the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010, publicly traded companies must hold shareholder-advisory votes on executive compensation annually, biennially, or triennially, at shareholders' discretion. See Pub. L. No. 111-203, 124 Stat. 1376, §951 (2010).

- See Reports and Findings, http://www.proxymonitor.org/Forms/reports_findings.aspx.

- 558 U.S. 310 (2010).

- See Adam Liptak, Supreme Court Gets a Rare Rebuke, in Front of a Nation, N.Y. TIMES, Jan. 28, 2010, http://www.nytimes.com/2010/01/29/us/politics/29scotus.html?_r=0.

- See Pete Kasperowicz, Sanders Proposes Amendment to the Constitution That Would Limit Free Speech, THE HILL, Dec. 9, 2011, http://thehill.com/blogs/floor-action/senate/198343-sanders-offers-constitutional-amendment-to-strip-corporations-of-first-amendment-rights.

- See Letter from Committee on Disclosure of Corporate Political Spending to Elizabeth M. Murphy, Secretary, Securities and Exchange Commission (Aug. 3, 2011), http://www.sec.gov/rules/petitions/2011/petn4-637.pdf. For a response, see James R. Copland, Against an SEC-Mandated Rule on Political Spending Disclosure: A Reply to Bebchuk and Jackson, 3 HARV. BUS. L. REV. 381 (2013).

- See Francine McKenna, Schumer Says SEC's White Is "Poisoning" Politics, MARKETWATCH, June 15, 2016, http://www.marketwatch.com/story/schumer-says-secs-white-is-poisoning-politics-2016-06-14.

- Andrew Taylor & Marcy Gordon, Democrats Block SEC Nominees, U.S. NEWS & WORLD RPT., Apr. 7, 2016, http://www.usnews.com/news/business/articles/2016-04-07/democrats-block-sec-nominees-over-political-money-fight. The principal author of this report, James R. Copland, went to law school with one of the nominees, Hester Peirce, whom he considers a friend.

- Although corporate governance in the U.S. is mostly governed by substantive state law, cf. Del. Code Ann., tit. 8, § 211(b) (2009) (noting that in addition to the election of directors, "any other proper business may be transacted at the annual meeting"), the federal SEC controls the process of proxy solicitation under rules promulgated under section 14(a) of the Securities and Exchange Act of 1934, 4, Pub. L. No. 73-291, ch. 404, 48 Stat. 881 (1934).

- See 17 C.F.R. § 240.14a-8 (2007).

- See Center for Political Accountability, About the CPA, http://politicalaccountability.net/about/about-us (last visited June 24, 2016).

- 2016 voting results include 219 of 250 companies to have held annual meetings by June 10. In determining shareholder support for shareholder proposals, the Manhattan Institute counts votes consistent with the practice dictated in a company's bylaws, consistent with state law. Some companies measure shareholder support by dividing the number of votes for a proposal by the total number of shares present and voting, ignoring abstentions. Other companies measure shareholder support by dividing the number of favorable votes by the number of shares present and entitled to vote—thus including abstentions in the denominator of the tally. Neither practice necessarily skews shareholder votes in management's favor: whereas the latter method makes it relatively more difficult for shareholder resolutions to obtain majority support, it also makes it more difficult for management to win shareholder backing for its own proposals, such as equity-compensation plans.

Shareholder-proposal activists prefer to exclude abstentions consistently in tabulating vote totals, without regard to corporate bylaws; See Heidi Welsh, Accuracy in Proxy Monitoring, HLS Forum on Corporate Governance and Financial Regulation (Sept. 16, 2013), https://corpgov.law.harvard.edu/2013/09/16/accuracy-in-proxy-monitoring-2 (critiquing the Proxy Monitor data set), which necessarily inflates apparent support for their proposals. But such a methodology is inconsistent with federal law. The SEC's Schedule 14A specifies that for "each matter which is to be submitted to a vote of security holders," corporate proxy statements must "[d]isclose the method by which votes will be counted, including the treatment and effect of abstentions and broker non-votes under applicable state law as well as registrant charter and bylaw provisions"—clearly indicating that corporations can adopt varying counting methodologies in assessing shareholder votes and that state substantive law governs the parameters of vote calculation. See Item 21, Voting Procedures, 17 C.F.R. § 240.14a-101, https://www.law.cornell.edu/cfr/text/17/240.14a-101. Under the state law of Delaware, where most large public corporations are chartered, "the certificate of incorporation or bylaws of any corporation authorized to issue stock may specify the number of shares and/or the amount of other securities having voting power the holders of which shall be present or represented by proxy at any meeting in order to constitute a quorum for, and the votes that shall be necessary for, the transaction of any business." Del. Gen. Corp. L. § 216, http://delcode.delaware.gov/title8/c001/sc07 (last visited Sept. 11, 2015). As a default rule, absent a bylaw specification, Delaware law specifies that "in all matters other than the election of directors," companies should count "the affirmative vote of the majority of shares of such class or series or classes or series present in person or represented by proxy at the meeting," id. at 216(4)—the precise inverse of shareholder-proposal activists' preferred counting rule.

The SEC staff has adopted a permissive standard that "[o]nly votes for and against a proposal are included in the calculation of the shareholder vote of that proposal," ignoring abstentions, SEC Staff Legal Bulletin No. 14, F.4., July 13, 2001, https://www.sec.gov/interps/legal/cfslb14.htm (last visited Apr. 8, 2016); but only for the very limited purpose of determining whether a proposal has met the "resubmission threshold" to qualify for inclusion on the next year's corporate ballot—a minimum 3 percent, 6 percent, or 10 percent vote, respectively, in successive years. See Amendments to Rules on Shareholder Proposals, Exchange Act Release No. 40,018; 63 Fed. Reg. 29,106, 29,108 (May 28, 1998) (codified at 17 C.F.R. pt. 240). Because this is a staff rule not voted on by the commission, because it exists for a limited purpose (with multiple rationales, including reducing workload in processing 14a-8 no-action petitions and adopting a permissive standard for ballot inclusion), and because it contravenes clear and long-standing deference to substantive state law in the field of corporate governance, the notion that this limited SEC staff vote-counting rule should dictate counting methodology, irrespective of state law and governing corporate bylaws, is untenable.

- See Fluor, http://www.fluor.com/pages/default.aspx (last visited June 23, 2016).

- See Taylor & Gordon, supra note 8.

- See Letter from Committee on Disclosure of Corporate Political Spending, supra note 6.

- Taylor & Gordon, supra note 8. Note that although Taylor and Gordon report that Schumer claimed that the proposed SEC rule would "force corporations like Koch Industries to reveal their political giving," the Koch companies are privately owned and thus not subject to the SEC's jurisdiction.

- See McKenna, supra note 7.

- Id.

- See Michael Chamberlain, Socially Responsible Investing: What You Need to Know, FORBES, Apr. 24, 2013, http://www.forbes.com/sites/feeonlyplanner/2013/04/24/socially-responsible-investing-what-you-need-to-know/#50868c655863 ("In general, socially responsible investors are looking to promote concepts and ideals that they feel strongly about").

- Pension plans are generally bound as fiduciaries under the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) to maximize share value in their pension management. See 29 C.F.R. § 2509.08-2(1) (2008). However, those affiliated with religious organizations are exempt from this requirement. See 29 U.S.C. § 1003(b).

- See, e.g., Devon Energy Corp., Proxy Statement Pursuant to Section 14(a) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, proposal no. 6 (Apr. 27, 2016), https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/1090012/000119312516556736/d130272ddef14a.htm#tx130272_127.

- Before rounding, the average shareholder vote for political spending and lobbying proposals fell year over year, by about 0.5 percentage points.

- Fluor Corp., Proxy Statement Pursuant to Section 14(a) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, proposal no. 4 (Mar. 10, 2016), https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/1124198/000104746916010949/a2227438zdef14a.htm#ek41601_proposal_4__#151;_stockholder_proposal.

- See More than 70 Years of Government Project Experience—Fluor, http://www.fluor.com/client-markets/government/pages/default.aspx (last visited June 24, 2016).

- See Kathryn Gansler, Center for Political Accountability, Corporate Political Spending

Transparency and Accountability Report, Mar. 30, 2016, http://files.politicalaccountability.net/reports/transparency-and-accountability-2/2016_Fluor_Corp_Transparency_Report.pdf (last visited June 24, 2016).

- See Zachs Equity Research, Fluor (FLR): Q1 Earnings Miss, Revenues Beat; Outlook Cut, May 6, 2016, http://finance.yahoo.com/news/fluor-flr-q1-earnings-miss-132501867.html.

- See James R. Copland et al., Proxy Monitor 2012: A Report on Corporate Governance and Shareholder Activism 20–23 (Manhattan Inst. for Pol'y Res., Fall 2012), http://www.proxymonitor.org/pdf/pmr_04.pdf.

- See id. at 23 (citing Bryan Caplan, THE MYTH OF THE RATIONAL VOTER [2007]).

- See ISS, 2016 United States Summary Proxy Voting Guidelines 66 (Dec. 18, 2015), https://www.issgovernance.com/file/policy/2016-us-summary-voting-guidelines-dec-2015.pdf.

- Copland et al., supra note 27, at 23.

- For further elucidation of this argument, see Copland, supra note 6.

- See Center for Political Accountability, Our Impact, http://politicalaccountability.net/impact (emphasis in original) (last visited June 24, 2016).

- A 2012 strategy memorandum from the left-leaning advocacy group Media Matters for America expressed an "end goal" for "corporate transparency" efforts of "mak[ing] the case that political spending is not within the fiduciary interest of publicly traded companies and therefore should be limited" (on file with author).

- For a discussion of various attacks on corporate political speech in this context, see Copland, supra note 6, at 405–6. See generally Kimberley Strassel, THE INTIMIDATION GAME: HOW THE LEFT IS SILENCING FREE SPEECH (Twelve, 2016).

- See Tracie Woidtke, Public Pension Fund Activism and Firm Value 3 (Manhattan Institute for Policy Research, Sept. 2015) (showing that firms targeted by the New York State Common Retirement Fund with social-issue shareholder proposals during DiNapoli's tenure subsequently had lower share valuations than other firms in the S&P 500),

https://www.manhattan-institute.org/html/public-pension-fund-activism-and-firm-value-7871.html.

- See Barry B. Burr, 5 Companies to Disclose Political Spending Following N.Y. State Common Proposals, PENSIONS & INVESTMENTS, Mar. 23, 2016 (noting that the "New York State Common Retirement Fund withdrew shareholder proposals after reaching agreements with five companies on reporting their political spending"), http://www.pionline.com/article/20160323/ONLINE/160329942/5-companies-to-disclose-political-spending-following-ny-state-common-proposals.